The Vagus Nerve & Breathwork: A Guide to Nervous System Regulation

Updated: 21/01/2026

Have you ever noticed how taking a slow, deep breath can ease tension almost instantly?

In moments of stress, the breath often shifts things before we’ve had time to think about it. If you work with breathwork, you’ve probably seen this happen again and again, in yourself and in the people you support.

At the centre of this response is the vagus nerve. It’s a long, wandering nerve that connects the brain with the heart, lungs, and gut, helping the body sense whether it’s safe or under threat. Because the vagus nerve is closely linked with breathing, even small changes in how we breathe can have a big impact on how we feel, physically and emotionally.

Understanding the vagus nerve helps explain why breathwork can support calm, emotional regulation, and resilience. In this article, we’ll explore what the vagus nerve is, why it’s so important in trauma-informed breathwork, and how gentle, conscious breathing practices can help support vagal tone and nervous system balance over time.

Quick Links

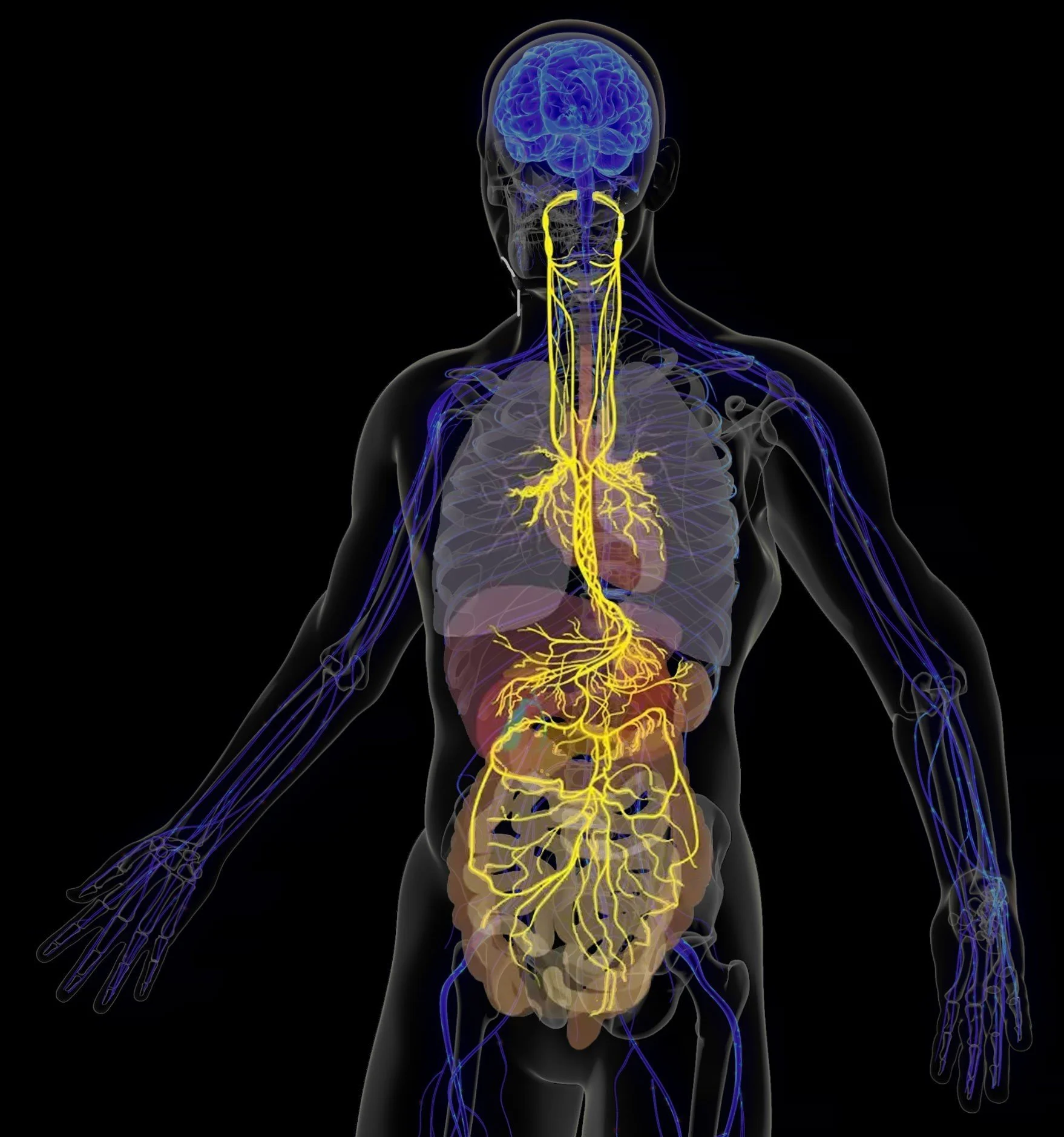

The Vagus Nerve (In Yellow)

💡 Short Answer: The Vagus Nerve & Breathwork

The vagus nerve is a key pathway that helps your body know when it’s safe.

It connects your brain to your heart, lungs, and gut, and plays a central role in calming the nervous system.

When breathing is slow, steady, and comfortable, it sends signals through the vagus nerve that help the body shift out of stress and into regulation. This is why breathwork can feel grounding, settling, or relieving, sometimes even before you consciously notice a change.

You don’t need to “do” breathwork perfectly for it to help. Gentle awareness, choice, and pacing are often enough.

What is the Vagus Nerve?

The vagus nerve is one of the most important communication pathways in the body, even though many people have never heard of it.

It’s a cranial nerve, which means it starts in the brain rather than the spinal cord. There are twelve cranial nerves in total, each with a specific role, from vision and hearing to facial movement and swallowing. The vagus nerve is the tenth cranial nerve, often called cranial nerve X.

What makes the vagus nerve unique is how far it travels.

The word vagus comes from the Latin word vagari, meaning “to wander.” Unlike other cranial nerves that stay mostly in the head and neck, the vagus nerve travels down through the throat and chest and into the abdomen. Along the way, it connects with key organs including the heart, lungs, and digestive system.

Because of this wide reach, the vagus nerve plays a major role in regulating many automatic processes that happen without us having to think about them, such as:

Heart rate and blood pressure

Breathing rhythms

Digestion and gut function

Inflammatory and immune responses

In simple terms, the vagus nerve helps the body stay balanced.

The Vagus Nerve and the Nervous System

The vagus nerve is a central part of the parasympathetic nervous system, often described as the “rest and digest” branch of the nervous system. This part of the system helps the body slow down, recover, and repair after stress.

When the vagus nerve is active, it sends signals that help:

Slow the heart rate

Lower blood pressure

Support digestion and absorption

Reduce unnecessary inflammation

This is why activating the vagus nerve is closely linked with feelings of calm, safety, and relaxation.

A Two-Way Communication Channel

One of the most fascinating things about the vagus nerve is that it works in both directions.

Around 80% of the fibres in the vagus nerve send information from the body up to the brain, not the other way around. This means the brain is constantly receiving updates about what’s happening in the heart, lungs, and gut.

The remaining fibres carry messages from the brain back down to the body, helping regulate things like breathing patterns, heart function, and digestion.

This two-way flow is why the breath is such a powerful tool. When we change how we breathe, we send clear signals to the brain about safety, stress, or ease, and the nervous system responds.

Why This Matters for Breathwork

Because the vagus nerve is so closely connected to breathing, gentle changes in breath can directly influence nervous system state. Slow, steady breathing can support the body in shifting out of fight-or-flight and into a more regulated, grounded state.

This is one of the reasons breathwork can feel so effective, even when nothing else seems to help. We’re not trying to “think” our way into calm, we’re working with the body’s own communication systems.

For trauma-informed breathwork, understanding the vagus nerve helps us move at the pace of the nervous system, prioritising safety, choice, and regulation rather than intensity or force.

The Vagus Nerve and Emotional Health

Emotional health isn’t just something that happens in the mind, it’s deeply rooted in the body. The vagus nerve plays a key role in this connection, acting as a bridge between how we feel emotionally and what’s happening physiologically.

When the vagus nerve is working well, the nervous system has more flexibility. This is often described as healthy vagal tone, the ability to move out of stress and return to calm without getting stuck. People with good vagal tone tend to feel more resilient, emotionally steady, and able to respond to life’s challenges without becoming overwhelmed.

When vagal tone is lower, it can feel much harder to regulate emotions. People may notice increased anxiety, low mood, irritability, or difficulty settling after stress. This doesn’t mean something is “wrong”, it simply reflects how the nervous system has adapted to past experiences.

Polyvagal Theory: Understanding Our Emotional States

Polyvagal Theory, developed by Dr Stephen Porges, helps us understand why we respond the way we do under stress and how the vagus nerve shapes our emotional world.

Rather than the nervous system having just “calm” and “stressed” modes, Polyvagal Theory describes three main states that we move between throughout the day:

Ventral vagal (safety and connection)

This is the state where we feel grounded, present, and able to connect with others. Emotions feel manageable, communication flows more easily, and the body feels relatively settled.Sympathetic (fight or flight)

When the nervous system senses danger or pressure, it shifts into action. This can show up as anxiety, restlessness, racing thoughts, irritability, or urgency. The body is mobilised to respond.Dorsal vagal (shutdown or collapse)

When stress feels overwhelming or inescapable, the system may move into a protective shutdown. This can feel like numbness, disconnection, fatigue, or emotional flatness.

These states are not choices or personality traits, they are automatic, protective responses shaped by the nervous system. The vagus nerve plays a central role in moving between them.

How the Vagus Nerve Supports Emotional Regulation

The vagus nerve helps the nervous system move back toward safety after stress. It influences emotional health through its impact on:

Heart rate and heart rate variability (HRV), which are linked to emotional resilience

Breathing rhythms, which naturally shift with stress, fear, calm, or connection

The gut–brain connection, where digestion, inflammation, and mood are closely connected

Because around 80% of vagus nerve fibres carry information from the body to the brain, emotional experience is constantly shaped by physical signals. This helps explain why emotions can change when the body feels safer — even without talking or analysing what’s happening.

Feeling Safe Enough to Feel

One of the vagus nerve’s most important roles is helping the body recognise when it is safe. When the nervous system senses safety, emotions become easier to experience without being overwhelming.

In this state, people may notice they feel:

More present and connected

Less reactive or defensive

Better able to stay with emotions as they arise

For many people, especially those with trauma histories — this sense of safety hasn’t always been available. The nervous system may have learned to stay on high alert or to disconnect as a form of protection.

Why This Matters in Trauma-Informed Breathwork

Trauma-informed breathwork recognises that regulation comes before reflection. Before insight, processing, or change can happen, the nervous system needs to feel safe enough to engage.

By working gently with the breath, we can stimulate the vagus nerve and support the nervous system to soften, settle, and regain flexibility. This doesn’t force emotional release or catharsis, it creates the conditions where regulation and emotional resilience can grow naturally over time.

Breathwork becomes a way of meeting emotions through the body first, allowing emotional health to be supported from the inside out.

How Breathwork Stimulates the Vagus Nerve

Breathwork supports the vagus nerve in a very direct, physical way. We’re not trying to “relax” the body through effort or positive thinking, we’re sending clear signals of safety through the breath.

When breathing slows, deepens, or becomes more rhythmic, the body receives the message: it’s okay to soften now.

Here are the main ways this happens.

Breathing Sends Safety Signals to the Brain

Inside the lungs and blood vessels are tiny sensors that notice changes in pressure and rhythm. When we breathe slowly and steadily, these sensors are gently activated.

They send messages up through the vagus nerve to the brainstem, signalling that the body is safe. In response, the nervous system begins to ease out of fight-or-flight and into a more regulated state.

This is why slow breathing can feel calming almost immediately, the body responds before the mind has time to catch up.

The Diaphragm Plays a Key Role

The diaphragm is the main muscle involved in breathing, and it sits just below the lungs. When breathing is shallow or fast, the diaphragm barely moves and the vagus nerve receives very little stimulation.

When we breathe more deeply, especially into the belly, the diaphragm moves fully. This movement gently massages internal organs and stimulates the vagus nerve, sending calming signals throughout the nervous system.

This is one reason diaphragmatic (belly) breathing is often used as a foundation in trauma-sensitive breathwork.

Slower Breathing Supports Nervous System Balance

Breathwork also affects something called heart rate variability (HRV), the natural variation in time between heartbeats. Higher HRV is linked to better vagal tone and greater nervous system flexibility.

Slow, intentional breathing increases HRV, helping the body become more adaptable. Over time, this supports resilience, the ability to respond to stress and then return to balance more easily.

Rather than trying to stay calm all the time, the nervous system learns how to move more fluidly between states.

Rhythm Matters More Than Force

Breathing practices that focus on rhythm, such as steady inhale and longer exhale, help stabilise the nervous system. When the breath becomes rhythmic, the heart, lungs, and brain begin to work together more coherently.

Breathing at around five to six breaths per minute is often especially supportive for the vagus nerve. This doesn’t need to be exact or forced, even gentle slowing can make a meaningful difference.

Importantly, this kind of breathwork is about pacing, not pushing.

Why This Feels So Supportive

Because the vagus nerve connects the breath, heart, gut, and brain, breathwork can create whole-body shifts rather than surface-level calm.

People often notice:

A sense of settling or grounding

Slower heart rate

Deeper, easier breathing

Feeling more present or connected

Over time, consistent practice helps retrain the nervous system to recognise safety more easily.

A Trauma-Sensitive Reminder

Not everyone experiences breathwork as calming straight away. For some people, especially those with trauma histories, slowing the breath can initially feel uncomfortable or unfamiliar.

This is why trauma-sensitive breathwork emphasises:

choice

gentle pacing

staying within a comfortable range

Even simple breath awareness, without changing anything, can begin to support vagal tone. There is no need to force relaxation or push through discomfort.

Breathwork works best when it meets the nervous system where it is.

Best Breathing Techniques for Vagal Tone

When it comes to supporting the vagus nerve, how we breathe matters more than how much or how hard. Techniques that are slow, steady, and comfortable tend to be the most supportive for vagal tone.

There’s no single “best” breath for everyone. The most effective practice is always the one that feels safe and accessible to your nervous system in that moment.

Here are some commonly used breathing approaches that are known to support vagal tone.

Slow Diaphragmatic (Belly) Breathing

This is one of the most accessible and grounding ways to support the vagus nerve.

By breathing gently into the belly, the diaphragm moves more fully, stimulating the vagus nerve and sending calming signals to the brain. The chest and shoulders stay relatively relaxed, and the breath feels steady rather than forced.

This kind of breathing is often used:

at the beginning or end of sessions

during moments of stress or overwhelm

as a daily regulation practice

Even a few slow breaths can make a noticeable difference.

Extended Exhale Breathing

Lengthening the exhale slightly longer than the inhale is a simple way to encourage the nervous system to settle.

The exhale is closely linked to the parasympathetic (“rest and digest”) response. When we gently slow and lengthen it, the body often responds by softening tension and reducing arousal.

For example, breathing in for a count of four and out for a count of six can be supportive, but counting is always optional. What matters most is ease, not precision.

Coherent or Rhythmic Breathing

Coherent breathing involves finding a steady, comfortable rhythm, often around five to six breaths per minute, where the inhale and exhale are smooth and even.

This rhythm helps the heart, lungs, and nervous system work together more harmoniously, supporting vagal tone and emotional regulation.

It’s not about controlling the breath tightly. Instead, it’s about allowing the breath to find a natural, calming pace.

Alternate Nostril Breathing (Nadi Shodhana)

Alternate nostril breathing is a traditional practice that can support nervous system balance and focus.

When practised gently, without breath holds or strain, it can help stabilise the nervous system and support vagal activity. For some people, this technique feels very grounding; for others, it may feel more mentally engaging.

As with all breathwork, it’s best offered as an option rather than a requirement.

Box Breathing (with a Soft Focus on the Exhale)

Box breathing can be supportive for vagal tone when practised slowly and gently, particularly when the emphasis is on a relaxed exhale.

Rather than strict counting or long holds, trauma-sensitive approaches often soften this technique, reducing or removing breath holds if they feel uncomfortable.

This can make box breathing more accessible for people who find breath holds activating.

Other Ways to Strengthen the Vagus Nerve

While breathwork is one of the most direct ways to support the vagus nerve, it works best as part of a wider picture. The nervous system responds to patterns of safety over time, not single techniques done perfectly.

Small, consistent experiences that help the body feel safe, connected, and supported can gently strengthen vagal tone.

Here are some simple, accessible ways this can happen.

Social Connection and Co-Regulation

The vagus nerve is closely linked to our ability to feel safe in connection with others. Warm, supportive relationships naturally stimulate the nervous system’s social engagement pathways.

This might look like:

spending time with people you feel comfortable with

sharing conversation or laughter

making eye contact with someone who feels safe

gentle connection with animals or pets

For facilitators, this is why how we show up matters. A calm voice, steady presence, and attuned listening can support regulation through co-regulation, even without doing anything “extra”.

Gentle, Mindful Movement

Movement can help release physical tension and support nervous system balance, especially when it’s slow, rhythmic, and non-striving.

Practices such as:

gentle yoga

mindful walking

stretching

tai chi or qigong

can all support vagal tone by helping the body feel more settled and fluid.

Unlike high-intensity exercise, which activates the sympathetic nervous system, gentle movement tends to signal safety and support parasympathetic activity.

Sound: Humming, Singing, and Vocalisation

The vagus nerve has branches connected to the throat and vocal cords, which means sound can be a surprisingly powerful regulator.

Humming, singing, chanting, or even gentle toning can stimulate the vagus nerve and support emotional regulation. Many people notice these practices feel soothing or grounding, even without understanding why.

This is one reason sound is often included in breathwork sessions, meditation, and group practices.

Cold Stimulation (Used Gently)

Brief exposure to cold, such as splashing cool water on the face or ending a shower with cool water , can stimulate the vagus nerve.

That said, cold exposure isn’t suitable for everyone. For some people, especially those with trauma histories or certain health conditions, it can feel overwhelming rather than regulating.

As with all nervous system practices, choice and pacing matter more than technique.

Mindfulness and Present-Moment Awareness

Practices that bring attention gently into the present moment can help calm the nervous system and support vagal tone.

This doesn’t need to be formal meditation. It might simply be:

noticing the feeling of your feet on the floor

paying attention to sounds around you

pausing to feel your breath without changing it

spending time in nature

These small moments of presence help the nervous system orient toward safety and stability.

The Vagus Nerve, Trauma, and Safety

When someone has experienced stress or trauma, whether recent or long past, their nervous system may have learned to stay on high alert or to shut down as a form of protection. These responses are not signs of something being broken. They are intelligent survival strategies shaped by experience.

The vagus nerve plays a central role in this process. When the nervous system doesn’t feel safe, vagal regulation can be disrupted, making it harder to settle, connect, or return to calm after stress. This can show up as anxiety, emotional numbness, overwhelm, fatigue, or difficulty feeling present.

From a trauma-informed perspective, the goal isn’t to force relaxation or push the nervous system into calm. Instead, it’s about gently restoring a sense of safety, one small step at a time.

Why Safety Comes First

For many people, especially those with trauma histories, practices that slow the body down can initially feel uncomfortable or even unsettling. Stillness, quiet, or inward focus may bring up sensations or emotions that feel too much.

This is why trauma-sensitive breathwork places such a strong emphasis on:

choice

pacing

consent

staying within a comfortable range

Supporting the vagus nerve is not about intensity or catharsis. It’s about helping the nervous system learn that it can move toward regulation without being overwhelmed.

Breathwork as a Gentle Support

When offered thoughtfully, breathwork can help the nervous system experience moments of safety and ease, sometimes for the first time in a long while. These small experiences matter. Over time, they can help rebuild nervous system flexibility and resilience.

This process is rarely linear. Some days regulation feels easier; other days it doesn’t. That’s normal. Healing and nervous system repair happen through repetition, patience, and kindness, not through doing things “right”.

The vagus nerve responds best to consistency and compassion, not pressure.

Where to Start (If This Feels Like a Lot)

If you’re new to this work, or if your nervous system feels sensitive, starting small is more than enough.

You might begin with just one of these:

Notice your breath for a few moments, without trying to change it

Slow your exhale slightly, if that feels comfortable

Place a hand on your chest or belly and feel the movement of breathing

Hum softly or sigh, noticing how your body responds

Spend a few minutes in nature or focusing on something soothing around you

Using this guided body scan and breath awareness meditation to assist you in a low pressure way.

There’s no need to do everything, and there’s no rush. Supporting the vagus nerve is about building a relationship with your body , one that’s based on listening rather than control.

If you’d like more structure or guidance, practising with a trauma-sensitive breathwork facilitator or joining a gentle, guided session can help you explore these practices in a supported way.

Above all, remember: your nervous system already holds the capacity for regulation and repair. Breathwork simply offers a way to reconnect with that innate intelligence, at a pace that feels right for you.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Vagus Nerve and Breathwork

-

Vagus nerve breathing is a way of using slow, intentional breathing to stimulate the vagus nerve. Techniques such as diaphragmatic (belly) breathing or extended exhalation activate parasympathetic pathways, which help the body shift into a calm, restorative state. Over time, this practice can improve vagal tone, supporting both emotional resilience and physical well-being.

-

When you breathe deeply, two things happen: baroreceptors in your lungs and arteries are gently stretched, and your diaphragm fully engages. Both of these actions send signals through the vagus nerve to the brainstem, telling your body it’s safe. This increases vagal activity, slows the heart rate, and helps calm the stress response.

-

Yes. The vagus nerve helps regulate breathing rhythms as part of the parasympathetic nervous system. When vagal tone is strong, breathing tends to be smooth and steady. If vagal function is impaired, breathing may feel shallow, irregular, or harder to regulate. Strengthening the vagus nerve through breathwork supports more consistent and calming breathing patterns.

-

Some of the most effective practices include:

Coherent breathing (about 5–6 breaths per minute)

These methods all improve vagal tone by activating parasympathetic pathways and enhancing heart rate variability (HRV).

-

Breathwork is one of the easiest daily practices, but it’s not the only one. You can also support vagal tone through:

Social connection with safe, supportive people

Gentle movement such as yoga, walking, or dancing

Humming, chanting, or singing

Short, gentle cold exposure (like a cool shower)

Mindfulness and grounding practices

These simple actions tell your nervous system that you’re safe, helping the vagus nerve reset and regulate more effectively.